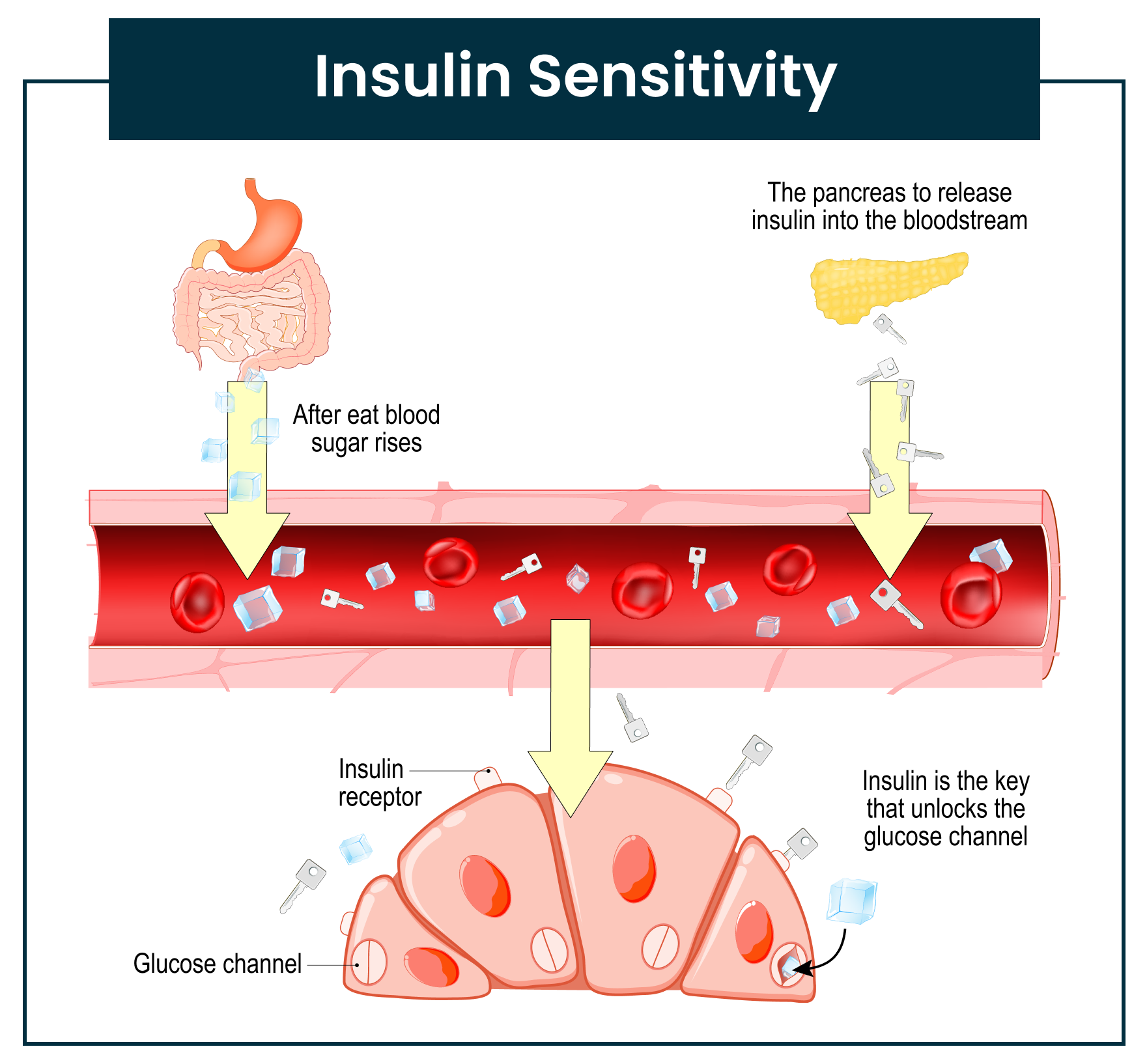

Insulin resistance (not good) vs. insulin sensitivity (good): what’s the difference? You may have heard about insulin resistance—a growing epidemic in the United States. It occurs when the body can no longer use insulin efficiently to perform its essential job: transporting energy from the food you eat (glucose) into your cells.

Imagine your cells are covered in plastic wrap or rust. Even though insulin (the “key”) is present, it can’t unlock the cell doors to let glucose in. This is insulin resistance.

On the other hand, insulin sensitivity is when those “locks” on your cells are clear—no rust, no saran wrap—allowing insulin to work effectively. Improving insulin sensitivity means gradually “cleaning” those locks so insulin can do what it was designed to do: help your body use energy efficiently.

Let’s look at three proven ways to increase insulin sensitivity.

1. Eat More Plants

Improving insulin sensitivity can be achieved by incorporating more whole, plant-based, low-fat foods into your meals. Plants are more than just a colorful side dish—they are powerful sources of antioxidants. When combined with fiber and essential micronutrients, plants become a “super tool” for managing mealtime blood sugar levels.

Eating plants daily can also help address several underlying factors that contribute to insulin resistance. Nutrient-dense foods like whole fruits, legumes, sweet potatoes, and whole grains are especially beneficial because they contain the ideal combination of micronutrients needed to metabolize sugar efficiently—that is, to help get glucose into the cells and convert it into energy.

Keep in mind that when you first begin including these foods, you might notice a temporary spike in blood sugar levels. This is normal and occurs because your body is adjusting to the plant-based carbohydrates, especially if you’ve previously avoided them.

As we address the root causes of insulin resistance, the micronutrients found in plant foods can play a critical role in regulating metabolism, gene expression, and the development and progression of many chronic diseases. A few key micronutrients to be mindful of when managing diabetes include chromium, zinc, magnesium, and vitamin B12..

Chromium

While the exact mechanisms remain unclear, chromium is an essential nutrient known to enhance insulin’s ability to transport glucose into cells (11). Since the body cannot produce chromium on its own, it must be obtained through diet and/or supplementation.

Some foods naturally higher in chromium include broccoli, green beans, grapes, and whole wheat flour. However, even when chromium is present in food, the amount is typically low—often less than 1 to 2 micrograms per serving. As a result, supplementation may be necessary to meet your daily needs.

If you’re considering supplementation, chromium picolinate is the most bioavailable form (12). Daily supplementation with 200 to 1,000 micrograms of chromium picolinate has consistently shown improvements in glucose tolerance and reductions in circulating insulin levels (12).

That said, it’s important to consult your healthcare provider before starting chromium supplements, as chromium can interact with certain medications, including insulin, metformin, and levothyroxine.

Zinc

Zinc is the second most abundant trace element in the human body after iron and is essential for the formation and stability of insulin. This vital nutrient also supports the health of our skin, teeth, bones, hair, nails, muscles, nerves, and brain function. Additionally, it plays a key role in effective wound healing.

If you consume alcohol or have uncontrolled diabetes, you may experience decreased zinc absorption and increased zinc loss through urine. For adults, the recommended daily intake of zinc is 11 mg for men and 8 mg for women (14).

Since our bodies can’t store zinc in large amounts, it’s important to include zinc-rich foods in your daily diet. To naturally boost your zinc intake, consider adding foods such as chickpeas, spinach, fortified foods, pumpkin seeds, oysters, mushrooms, beans, hemp seeds, and lean proteins.

There are also various types of zinc supplements available, including zinc gluconate, zinc acetate, zinc picolinate, zinc citrate, and zinc oxide. However, oral zinc supplements can interfere with the absorption of certain medications, so it’s always best to consult your primary care provider before starting supplementation.

Magnesium

Mag Magnesium plays a vital role in many bodily functions. It supports over 300 enzyme reactions, muscle movement, insulin regulation, and the proper functioning of blood cells (7). While it’s not a bad idea to have your magnesium levels tested, it’s important to understand that standard lab tests measure only about 1% of your total body stores. So, if your lab results show low magnesium, you’re likely very deficient. Conversely, even if your levels appear normal, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re not lacking magnesium.

Working with your dietitian—looking at your dietary habits, reviewing medications, and discussing your sleep and mental health—can provide better insight into your magnesium status. You may have low magnesium levels if your diet lacks magnesium-rich foods, if you have insulin resistance, or if you’re dealing with chronic diarrhea or alcohol use disorder (6,7). Diuretics or excessive magnesium loss through the kidneys can also lead to low levels. Lower magnesium levels have been linked to reduced insulin sensitivity (6), and studies suggest that increasing magnesium intake can be beneficial for people with diabetes (8).

For adults, the recommended daily intake of magnesium is 320–420 milligrams (15). If your diet is high in saturated fat, fructose, caffeine, or alcohol, you may need even more. To increase your magnesium levels, consider adding magnesium-rich foods like pumpkin seeds, avocados, chia seeds, leafy greens, and dark chocolate. You can also absorb small amounts of magnesium through the skin by taking Epsom salt baths.

It takes time for the body to restore adequate micronutrient levels after being in a state of insulin resistance, so patience is key. While plant-based foods support improved insulin sensitivity, processed foods, oils, and animal-based processed meats can have the opposite effect. Research shows that saturated and trans fats—often found in these foods—can increase the risk of developing diabetes or make it more difficult to manage (10).

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin that our bodies need but cannot produce on their own. It’s an essential nutrient that supports overall health and plays a key role in nerve function, blood sugar management, brain health, and the production of red blood cells. Without enough B12, the body cannot efficiently convert the carbohydrates, fats, or proteins we eat into usable energy.

A deficiency in B12 can also lead to a type of anemia in which red blood cells become abnormally large and unhealthy. Vitamin B12 helps form a protective coating around nerves—so when levels are low, it can result in neuropathy or even impair brain functions like memory and learning.

Another important role of B12 is its involvement in blood sugar regulation. People with diabetes may require more of it, especially since certain medications (such as metformin or antacids) can interfere with B12 absorption.

You can naturally increase your intake by adding nutritional yeast to meals, tossing shiitake mushrooms into a stir-fry, or using organic soy milk in a smoothie. Your dietitian may suggest checking your B12 levels and evaluating your dietary intake to determine whether supplementation is needed.

Choosing the right supplement is important, as not all forms are equally beneficial. A dietitian will likely recommend a methylated version—called methylcobalamin—which is the natural form of B12. It’s more readily absorbed and retained by the body compared to synthetic forms like cyanocobalamin, which may be less effective or potentially harmful in certain cases.

2. Move Your Body

Did you know that your body’s ability to use insulin can improve for up to 72 hours (about 3 days) after physical activity? Now you do! However, it’s important to note that this benefit can diminish within 5 days after your last workout (11). This is just one of many reasons why it’s important to move your body regularly—especially by doing physical activities you actually enjoy. When you enjoy the movement, you’re more likely to stick with it consistently.

Glucose is a key fuel source for your muscles. When you exercise, your muscles become active, and several metabolic processes are triggered. One of these involves GLUT-4, a special glucose transporter, moving to the surface of your muscle cells. If insulin is like a key and the insulin receptor is the lock, GLUT-4 acts like an additional lock that allows glucose to enter the cell. Exercise increases the number of these “locks,” making it easier for glucose to enter and be used for energy—ultimately helping lower blood sugar levels. This effect can last for hours after exercise, particularly after resistance training.

Another amazing fact: your muscles can absorb glucose without insulin during physical activity. When your muscles contract, they pull in glucose directly to use as fuel—almost like breaking down the door instead of needing a key. This means that exercise not only makes your cells more responsive to insulin but also reduces your body’s need for it in the first place.

It’s recommended to aim for at least two and a half hours of exercise or movement each week, which can be broken down into 30 minutes a day, about five days a week. Click here for creative ways to break up your exercise throughout the week. As movement becomes a regular part of your routine, your insulin sensitivity can improve.

You might wonder, which type of exercise is better—strength training (like lifting weights) or aerobic training (such as jogging or swimming)? The answer is both. Each type offers unique benefits and combining them can help you build a more well-rounded, sustainable fitness routine. Here’s why:

- Strength training helps improve your ability to carry out everyday tasks, supports healthy joint function, and preserves bone density as you age. As you build muscle, you create a metabolic powerhouse—muscle tissue burns more calories even while at rest. Strength training often involves using your body weight, free weights, weight machines, or resistance bands.

- Aerobic exercise boosts lung capacity, strengthens your heart and circulatory system, and builds endurance. These exercises typically involve large muscle groups in rhythmic, continuous motion over an extended period. Common examples include walking, running, swimming, cycling, stair climbing, or using an elliptical. Some are lower-impact than others, so explore a few to find what feels best for you.

So, what’s the best kind of exercise for your health? The truth is, the best exercise is the one you’ll do—and keep doing. If you’re not sure where to start, try something new: visit a nature park, join a fitness class, explore free online workouts, invite a friend to join you, or experiment with combining strength and aerobic routines. Let your interests guide you. Find what you enjoy, and build consistency from there.

3. Eating Window in Sync with Circadian Rhythm

You may have heard of “eating windows” in the context of intermittent fasting (IF). Many people come to Tula wanting to try IF but often misunderstand how to do it in a way that truly supports their health. Intermittent fasting (IF) refers to an eating pattern that alternates between periods of eating and fasting, which can range from 16 to 42 hours with little to no caloric intake (17). However, longer fasts should only be attempted when the body is in a “safe” state—meaning sleep quality is optimal, stress is low, and you’re already choosing healthy foods within your daily routine. Intermittent fasting is a broad term, and a quick internet search can lead to many misunderstandings about its proper use.

While there are various approaches to intermittent fasting, the way we recommend “eating windows” is not about skipping meals but aligning your eating habits with your body’s natural rhythm (circadian rhythm). Start by choosing an 8-hour window for eating during the day. This allows for moderate-sized meals and ensures your body receives all the necessary nutrients. Ideally, this 6-10 hour window should begin as or soon after the sun rises (or when you wake up, if you are a shift worker), syncing with your body’s natural processes, such as leptin release, which regulates appetite (18). Setting a hard stop for eating around 4 or 5 p.m. each day can help reduce emotional and mindless evening eating while also allowing your body to focus on producing melatonin for restful sleep. Healthy melatonin levels are associated with improved insulin sensitivity and the prevention of diabetic complications.

Eating within a 6-10 hour window, starting early in the day, has been shown to reduce inflammation, lower A1C, and help the body store and use energy more efficiently (22).

Outside of your circadian eating window, it is important to stay hydrated. You can still drink water, decaffeinated tea, or water flavored with natural sources like lemon or lime—but avoid sweeteners or sugar. This is because, while fasting, your body prioritizes breaking down complex molecules such as fats, proteins, and carbohydrates to release energy and maintain blood glucose levels. This process also continues while you sleep, breaking the “fasted state” when you eat your next meal. This time of not eating supports overall health and metabolism in many ways. During fasting, your body uses stored fat for energy, burning it more efficiently (18). By default, while we sleep, we are in a natural fasted state unless we eat upon waking.

What not to do: Many people skip breakfast when they first experiment with eating windows, but this can have negative effects. Skipping breakfast may cause the body to run on adrenaline and cortisol early in the day, which can disrupt insulin production and response. The body is naturally more sensitive to insulin in the morning, making this the best time for a nutrient-dense breakfast (21). A study found that skipping breakfast (not dinner) had no significant impact on weight loss or other metabolic parameters (18). Therefore, we recommend eating a nutrient-rich breakfast and making dinner the smallest meal of the day.

Take note: After closing your fasting window, you can further regulate hormone production by eating fiber-rich foods. This helps prevent a large insulin spike when breaking your fast. This can be challenging, especially if you’re very hungry and tempted to grab the first thing you see. To make it easier, consider prepping your “break the fast” meal ahead of time. Have pre-cut vegetables, prepared proteins, or fresh fruit on hand for a quick, healthy snack. Remember, eating within a circadian rhythm doesn’t mean you can eat unhealthy foods during your eating windows. It’s essential to focus on nutrient-dense foods to fuel your body and maintain optimal health.

Although there are many benefits to fasting, it’s not for everyone. Be sure to consult with your healthcare provider before starting intermittent fasting, especially if you are on medications, such as those for diabetes, as fasting may affect how they work. It’s important to monitor your blood sugar to prevent hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Certain groups should avoid intermittent fasting, including children, adolescents, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and adults over 75 (18).

Increasing insulin sensitivity is crucial for overall health and well-being. By making conscious choices in your diet and lifestyle—like incorporating nutrient-dense foods and regular exercise—you can take significant steps toward improving your body’s insulin response. Embracing these positive changes not only helps manage blood sugar levels but also reduces the risk of chronic diseases. Every small effort counts, and with perseverance, you can achieve a healthier, more vibrant life.

Sending Health Your Way!

The Tula Clinical Team

Reviewed by:

Aubree RN, BSN

Austin MS, RDN, CSR, LDN, CD

Tula Takeaways |

|---|

| 1. Magnesium Intake: Magnesium is crucial for over 300 enzymatic reactions, including insulin regulation. Low magnesium levels are linked to reduced insulin sensitivity. Include magnesium-rich foods like pumpkin seeds and spinach in your diet to support your body’s insulin function. |

| 2. Nutrient-Dense Diet: Transition to a diet rich in whole, plant-based, low-fat foods. Initially, your blood sugar may spike as your body adjusts to these healthy carbohydrates. However, foods like fruits, legumes, and whole grains are packed with micronutrients that aid in sugar metabolism, ultimately helping to combat insulin resistance. On the other hand, processed foods and animal-based meats, which are high in saturated and trans fats, can exacerbate diabetes risk. Remember, you can only make so many changes at once. Ask yourself, “Which of these would I like to start with?” Slow and steady change is key. Please consult with your provider before starting a new nutrition or exercise plan. Your safety and health should always be a priority. |

| 3. Find Happiness: Remember to find what brings you happiness. Take note of how it feels when you incorporate some of these insulin-sensitizing strategies into your days! |

The LIVE TULA blog is informational and not medical advice. Always consult your doctor for health concerns. LIVE TULA doesn’t endorse specific tests, products, or procedures. Use the information at your own risk and check the last update date. Consult your healthcare provider for personalized advice.